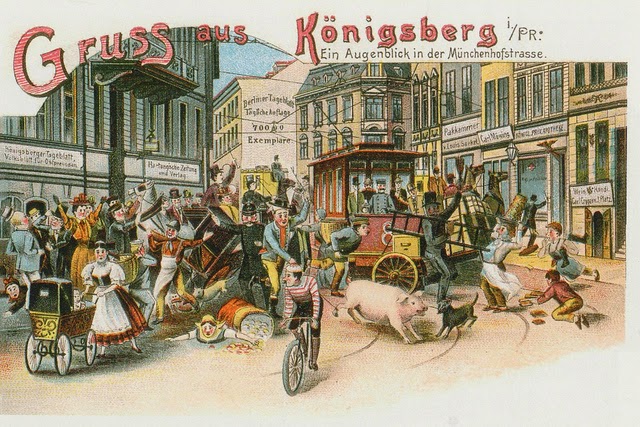

This post continues on from our biography of Hegel's contemporary Herbart and discusses his general view of metaphysics and method. We use Mauxion's La Métaphysique de Herbart (1894). The above is a picture of Old Königsberg, the former capital of East Prussia, where Herbart lectured as successor of Kant.

Chapter 2

General Characterization and Principal Divisions of Metaphysics

Herbart paid considerable attention to metaphysics, though he also communicated his ideas on education and psychology. Here we focus on the metaphysical principles that orient his thought. Four of his books are relevant here:

- Principal Points of Metaphysics (1809)

- Metaphysical Principles of the Theory of Attraction of Simple Elements (1812)

- Textbook for Introduction to Philosophy (1813)

- General Metaphysics (1828-29)

The last of these is the most significant. The development of doctrine over the years that is so apparent in Fichte and Schelling is not found in Herbart. He did not respond to criticism by changing his mind.

On Herbart's view, metaphysics takes contradictory concepts thrown up by experience and corrects them by completing them. It is thus “the art of understanding experience rightly” (Met. Princ.), in other words, removing contradictions. This characterization is valid for Parmenides’ theory of motion, Plato on comparison, Aristotle’s theory of a First Mover and Kant’s antinomies of pure reason. [This is of interest to me in relation to Hegel as it suggests that the significance Hegel attributes to contradiction is not an isolated or idiosyncratic theory, but something influenced by the general philosophical concerns of the day.]

Herbart owes this idea, not to historical observation alone, but to his teacher Fichte. In the Wissenschaftslehre, there is a contradiction implied by the opposition of self and not-self in the self. This gives rise to other contradictions through attempts to resolve it. Herbart includes here the idea of the self as identity of subject and object (which appears in Hegel’s Logic). Herbart himself says that he began his metaphysics from inquiring into the self (Von der Untersuchung des Ich bin ich wirklich ausgegangen. (38)).

Experience bears witness to a multiplicity of beings and not simply to the unity of consciousness. Herbart says of his metaphysical standpoint:

I do not stand on the mountain peak of the [Fichtean] self, but rather my base is the breadth of experience as a whole. Ich stehe nicht auf der einzigen Spitze des Ich, sondern mein Basis ist so breit wie die gesammte Erfahrung. (39, Psych. als Wissen., Preface)

His view of contradiction is different from Hegel, for Hegel abandons traditional (i.e. Aristotelian) logic to proclaim the “identity of contradictions”. Thus Hegel considers it possible to exalt both freedom and reason, for example, as social values and predicates of the Absolute.

In addition to the above, metaphysics, even in the absence of contradiction, can seek a complete and total explanation of things.

As for the principal divisions of philosophy, Herbart understands these as:

- Methodology (order of questions, method);

- Ontology (the ideas of substance and cause);

- Philosophy of Nature (theory of continuity in space, time and movement) and

- Ideology (psychology and the refutation of idealism).

We discuss the first of these below and will cover the others in separate posts.

Chapter Three

Method

We turn first to philosophical method, on which Hegel had little to say, his principal observation being that his method was “identical with the content”.

We have established that metaphysics seeks an improvement or perfection of cognition. Hence the first step of metaphysical should be to examine the materials of our current knowledge.

The given

|

| The experientially given in Königsberg |

What then is given in experience? Common sense replies – things and their changeable properties. But here scepticism finds contradiction: between the senses and between the senses and reason. It denies that things as they appear are the same what they truly are in themselves. This is also the view of metaphysics, notes Herbart.

Herbart had studied Sextus Empiricus and, like Hegel, seems to draw sceptical arguments from him. The modern scepticism of Hume, Herbart thinks, derives from his analysis of causality, substance and spatiality. Herbart thinks that these are necessary products of psychic mechanisms, not a priori forms, as in Kant. [We will discuss this in our posts on Herbart's theories of nature and psychology.]

In general, Herbart rejects "poeticising philosophers" (dichtenden Philosophen) and dreamers for more rigorous thought.

Progress

The second stage of method then, arises from the question of how to move from what is given to what is real? The relation of principle to consequence implicit in this seems also to be a contradiction: the consequence must be both contained in the principle, but also be something new. Take for instance syllogism: the major premiss (e.g. "All men are mortal") can be seen as containing the conclusion ("Socrates is mortal"). The minor premiss (e.g. "Socrates is a man") however is new and the arrangement of the major and minor is also new. We need two elements in the principle and two in the conclusion. Syllogism presupposes matters already arranged and so does not contribute greatly to extend knowledge.

Like Descartes and Kant (but in contrast to Wolff), Herbart distinguishes mathematics from logic. In Pythagoras’ theorem, lines are added to enable comparisons to be drawn and the conclusion drawn. In algebra, terms are replaced by equivalents. In general, we interpret by substitution; and make progress by reference to a goal (in mathematics, the “problem”). Herbart thinks that metaphysics proceeds analogously. This is what he means by “completion of concepts” (Ergänzung der Begriffe). However in algebra, only changes of form are involved.

In metaphysics, substitution carries with it the possibility of error. It needs a stimulus and a guide to make progress. Some say that “reason” may fulfil this role. Herbart rejects this as involving a theory of mental faculties that he rejects and which in his opinion vitiated Kant’s thought. He nevertheless seeks a concept with a principle of development in it (ein werdender Begriff). Such a contradictory concept is not an arbitrary formation (e.g. a square circle), nor something merely apparent that is resolved by logical analysis. It rather results necessarily from the given and logical analysis only clarifies its nature. [We may think here of the attempts by linguistic philosophy to talk away issues like free will.]

Herbart wishes neither to accept such contradictory concepts lazily, nor to reject the principle of non-contradiction. [Here there is perhaps a contrast with Hegel. At any rate, it is clear that the analysis of contradiction was not something peculiar to Hegel, or even Kant and Hegel alone. Something of the same idea is expressed in Leibniz dictum that the nature of freedom and the composition of the continuum were two labyrinths of the human mind.] Let us suppose a contradictory concept A, which contains M and N, which are mutually inconsistent. M and N are given together, but can only be thought separately. Thus:

When A is given, M and N must be identical; but

When A is thought, M and N must not be identical.

We must then suppose two elements in M, one identical and the other not identical with N. Let us call them M1 and M2. As both comprising M, these are identical with each other (we might proceed to further distinctions within M1, & so on). This can only be resolved if we suppose that, although each M is not identical to N individually, they are so as a whole. This identity generally involves a mutual modification of the M’s.

Let us take syllogism as an example. The putative contradiction is that the conclusion must be both identical (contained in) the principle, yet different from it, for syllogism is not a mere tautology. Here our M1 and M2 are the major and minor premisses: both together lead to the conclusion. Herbart proposes a “method of relations” (Methode der Beziehungen) to determine the original contradictory concept and its resolution.

As we have seen, his original examples of these concepts were found in analysis of the idea of Self. This he then thought he might generalize. For Fichte, the fundamental concept was the Self as identity of subject and object (der Ich als Identität des Subjects und des Objects). This is not the everyday idea of Selfhood, but it does arise from philosophical reflection. In grammar, we speak of ourselves only in the first person. We do represent ourselves to ourselves, alongside all other objects, but in the case of ourselves, we are both represented and representer. The Self also appears as wholly present at any given moment. [This analysis comes up again in the Refutation of idealism: see out forthcoming post on psychology.]

Let us then take the object. An object of consciousness is in general a representation. In the representation of the Self, one element is identical to the subject, another is not. The contradiction of the “subject-object” (a term taken up by Hegel in his Logic of the Concept) thus relates to the object (now distinguished into M1 and M2). There is further in the Self a multiplicity of representations, both simultaneous and successive. These together, thinks Herbart, may be equivalent to the subject, but on what condition? Only if they mutually cancel each other. He writes:

The manifold ideas must transform each other, for the self to be possible. (Es müssen also die mannigfaltigen Vorstellungen sich einander aufheben, wenn die Ichheit möglich sein soll.) (54) [Note here the Hegelian aufheben.]

How does this compare to Fichte? We find that he too resorts to divisibility (Wissenschaftslehre 1.3).

If we attain the real by this method, we must then use our knowledge to explain phenomena (Herbart's ontology), further determine the real (philosophy of nature) and its representation (ideology). This is the plan we will carry through in the following posts.

No comments:

Post a Comment